For many IFR pilots today, flying a GPS approach is second nature. Among the most capable options is the LPV approach, which offers ILS-like lateral and vertical guidance—but with far wider availability. Thanks to WAAS-enabled GPS, pilots can fly precision-style approaches at thousands of airports that don’t have an ILS installed.

In this video tip from Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course, we’ll break down the key differences between a GPS LNAV and LPV approach, and demonstrate step-by-step how to fly an LPV using the Garmin GTN 650 navigator.

Ready to sharpen your IFR skills even further? Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course combines over 13 hours of in-flight HD training with powerful written test prep tools—everything you need to build confidence and earn your rating.

https://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/26093023/Video-Tip-How-to-Fly-an-LPV-Approach-with-a-Garmin-GTN-650.png10001250IFR Focus Teamhttps://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/14115136/IFR-Focus-Logo_White_Blue_Web-01.pngIFR Focus Team2025-10-03 08:55:402025-10-03 09:21:11Video Tip: How to Fly an LPV Approach with a Garmin GTN 650

Scenario Picture this: you’re flying an ILS approach right down to the absolute minimums. At 200 feet above the ground, the only thing you can see are the approach lights flashing through the fog. You quickly run through FAR 91.175 in your head and remind yourself: yep, this means you’re allowed to keep going down to 100 feet above the touchdown zone.

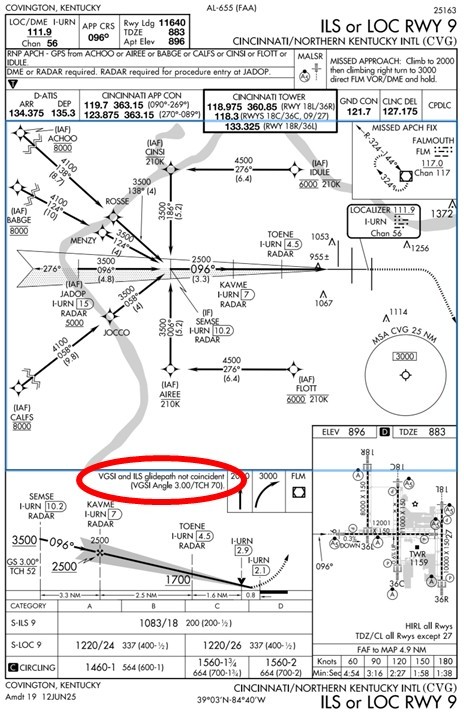

As you pass through 100 feet AGL, the runway threshold and touchdown zone lights start to poke through the fog—just enough to line things up. You glance left to check the PAPI and, at the same time, keep an eye on your instruments. That’s when you notice something weird: the glideslope says you’re right on path, but the PAPI shows you’re just a little low.

So now you’ve got a decision to make: • Do you trust the instruments and continue to land? • Or do you play it safe and go around?

Hard IFR vs. the Checkride This is where real-world IFR flying separates itself from the checkride. The ride feels almost scripted: constant vectors to final, the same familiar approaches, and airports you’ve probably flown into before, even in VFR. You usually know the terrain, the obstacles, and what to expect.

But out in the real world, you don’t always get that luxury. Sometimes you’re flying into an unfamiliar airport, with little margin for error, and the only thing that keeps you ahead of the airplane is a solid approach briefing. And that briefing really should start well before you even sit down in the cockpit.

Why the Notes Section Matters One of the most overlooked parts of the approach plate is the notes section. A lot of pilots skim right past it, but that’s where some of the most important “gotchas” are hiding—the limitations, restrictions, and curveballs that could turn an otherwise normal approach into an unexpected go-around.

If you take just a little extra time to brief those notes, you’ll head into the approach with clear expectations, less confusion, and fewer last-second decisions when workload is already maxed out.

Turning Notes into Action One of the easiest examples is when you see:

“VGSI and ILS glidepath not coincident.”

I’ve heard plenty of pilots brief that by simply reading the words out loud, but that doesn’t really prepare you for what it means when you break out. A better way is to dig a little deeper. Compare the threshold crossing height (TCH) of the VGSI (like the PAPI or VASI) with the TCH listed for the ILS glideslope in the profile view.

Now you can brief it with actual meaning:

“The VGSI and ILS glidepath are not coincident. The glideslope TCH is 54 feet, while the VGSI is 70 feet. When we break out, I expect to see three red and one white on the PAPI if we’re on the ILS glidepath. If I see that, we continue. But if I see four reds, that’s an immediate go-around.”

The Payoff See the difference? By briefing exactly what you expect to see, you’ve removed uncertainty from the picture. You know what’s normal, you know what’s not, and you know what action to take. That’s how you avoid hesitation in a high-stress, low-visibility moment. Instead of just reading a note, you’ve turned it into a practical risk management tool.

👉 Want a simple way to make your own approach briefings clear and organized? Check out this video where I walk through the ILS10R Approach into the Columbus International Airport (KCMH). Use it as a template the next time you fly IFR, and you’ll never look at the notes section the same way again.

https://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/24123434/Copy-of-whats-wrong.png10001250James Oniealhttps://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/14115136/IFR-Focus-Logo_White_Blue_Web-01.pngJames Onieal2025-09-30 08:55:492025-10-03 13:51:50Don’t Just Read the Notes—Use Them

Welcome to the latest edition of the Instrument Maneuver Spotlight series. Here we’ll highlight the various maneuvers you’ll practice during your instrument training and be expected to demonstrate during your checkride.

When the weather’s down and the runway is disappearing into the clouds, you can’t rely on outside references to stay on centerline and maintain control. That’s where the instrument takeoff comes in. In this maneuver spotlight, we’ll break down the step-by-step technique for conducting a safe and precise instrument takeoff.

Each maneuver is part of Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course and includes a narrated video animation, along with step-by-step instructions that include performance standards and common errors. Study them while on the ground or print them for quick reference in the airplane.

Welcome to “What’s Wrong?“, a new twist on aviation challenge quizzes. “What’s Wrong?” works just like a real flight: You’re in an airplane, flying along and there are clues to a potential problem right there in front of you—but it’s still on you to notice them and take action before it’s too late.

Under 14 CFR §61.57(c), instrument-rated pilots need to log at least six IAPs every six months to stay current and act as PIC under IFR or in weather below VFR mins. But not every approach counts—what matters are the conditions under which you fly it. Based on FAA guidance (InFO 15012), here’s the breakdown on what makes an IAP “loggable.”

The Four Ways to Conduct and Log IAPs

You can meet the requirement using:

Actual instrument conditions in an aircraft (flying in real IMC).

Simulated instrument conditions in an aircraft with a view-limiting device (like foggles) and a qualified safety pilot.

FAA-approved simulators or devices: Full Flight Simulator (FFS, Level A-D), Flight Training Device (FTD, Level 4-7), or Aviation Training Device (ATD, with a valid LOA). Be sure to check the LoA for what’s permissable.

A combination of the above, as allowed under §61.57(c)(4) or (5).

Key Conditions for Logging an IAP

To log it, the approach must meet all these criteria (from FAA legal interpretations):

Solely by reference to instruments: Whether in an aircraft or sim, you must fly using instruments only—no peeking outside.

Established on each required segment: Fly the full IAP from the initial approach fix (IAF) or feeder route, through the initial, intermediate, and final approach segments, down to the minimum descent altitude (MDA) or decision altitude (DA). (Exception: If radar-vectored to the final approach course or cleared otherwise by ATC, you can start from there.)

IMC (actual or simulated) to MDA/DA: The IMC must persist until you reach the MDA or DA when flying in sims or with foggles; however, if you break out to VMC on the final segment before or at MDA/DA, it’s still loggable as long as you’ve flown a portion of the final approach segment in IMC.

Under actual or simulated instrument conditions: Log actual or simulated instrument time alongside the approach— you can’t log an IAP without it.

Important Notes:

Safety Pilot Requirements: For simulated approaches in an aircraft, your safety pilot needs a current medical, must be rated in the category/class, and sit at the other controls. Log their name too (§§61.3(c), 61.51, 61.57(c), 91.109).

Missed Approach Segment: Not required to log the IAP, but practice it for proficiency!

Deviations for Safety: In simulated flight, if you deviate from the final segment (e.g., to avoid traffic) after passing the final approach fix (FAF), you can still log it.

Vectors and Clearances: Unless vectored or cleared to a specific point, execute the entire published IAP. A safety pilot or instructor can simulate ATC vectors.

Real-World Examples

You’re IFR-cleared for an ILS approach, flying solely by instruments in IMC. You stay established on all segments, pass the FAF, break out to VMC before DA, spot the runway, and land. Loggable? Yes—meets all conditions.

In VFR conditions, you’re under foggles with a CFII simulating ATC vectors to the GPS approach. You stay established through each segment, simulate IMC to MDA, break out, and land. Loggable? Yes—proper sim conditions and safety pilot.

IFR-filed but in VMC, under foggles with a safety pilot. Cleared for a VOR approach, you fly all segments to MDA, then execute a simulated missed and hold. Loggable? Yes—even without landing, as the missed segment isn’t required.

Take Our Survey

Have questions or a scenario to run by the IFR experts? Drop it in the comments or email us at IFRFocus@Sportys.com.

https://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/22121919/ask-an-expert-logging-approach.png10001250IFR Focus Teamhttps://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/14115136/IFR-Focus-Logo_White_Blue_Web-01.pngIFR Focus Team2025-09-19 08:55:272025-08-26 10:25:12Ask the IFR Expert: When Can You Legally Log an Instrument Approach?

In my younger days, my concept of weather data in flight was watching the clouds get darker as I trundled along the VOR radial, and wondering how rough the next 30 minutes might get. Now, I feel naked without in-cockpit weather, and will ask for deviations around denser precip just to keep from spilling my coffee.

But such confidence can get a harsh reality check now and then. Let me share a story of a flight that could be titled, “A Man with Two Watches.”

The route was direct Albany VOR (ALB), when two hours of hand-flying through IMC looked like it would end. (Yeah, that’s a photo in a Cirrus with the autopilot off. It’s not digitally altered. We all need the practice to stay sharp.) The iPad in my lap displayed ADS-B weather with stronger returns right of my course. The smoothest ride might have been to head a bit left (north), before crossing over ALB as planned. However, the XM weather on the MFD displayed a 20-mile wide area of low-energy returns left of the course, implying that a course southeast of ALB offered the smoothest ride. The ideal path using the MFD as my guide would be right on the edge of what I’d purposefully avoid using the iPad.

This dilemma wasn’t life-and-death. Perhaps it wasn’t even even spilling-the-coffee or not. For simplicity, I just stayed on course to ALB, feeling equivalent bumps to driving down a dirt road. That’s not the point.

It’s concerning that with only one of the weather presentations, I might have asked for a deviation with complete confidence. Had the returns been stronger, that misplaced confidence would have had real consequences. Using only one of the NEXRAD images, I would have asked for different things. Surely, both displays can’t be correct. Or, can they?

Let’s eliminate some potential sources for the discrepancy. The weather was not a rapidly changing convective environment, and the timestamps on both NEXRAD images were nearly identical. Both were “composite” reflectivity but came from different weather providers. We tend to simplify our thinking of NEXRAD as “base” or “composite” as if base always shows returns from the lowest part of the sky and composite displays all returns from the ground to the stratosphere. It’s not that simple.

Base reflectivity usually means “lowest tilt” reflectivity. This angle has the best chance of showing rain that would reach the ground, but it isn’t always low — once the beam is 125 miles from the station, the lowest tilt of the radar is looking about 17,000 feet in the air. That’s one of the reasons it’s essential to combine images from multiple stations into a mosaic, which is a single NEXRAD image.

Composite reflectivity adds multiple scan angles into the mosaic, but not necessarily all of them. What data is included — and what is left out — is part of the “secret sauce” different weather providers use, and part of the reason why we may see such different images.

The radar images, also, might not be as different as they first appear. The orientation on the MFD was heading-up. The iPad was track-up, but I had panned around, so now it was on some odd orientation. The MFD had a current direct-to ALB after a previous deviation. The iPad still displayed an old course because it hadn’t been updated.

When you rotate and scale the iPad image to match the MFD (above), the two images better align. The iPad still displays heavier returns where the MFD displays fewer, but the gaps line up better, and the logic of just staying on the course to ALB looks more consistent. Note to self: Think hard about the map scale and orientation when making any weather deviation based on in-cockpit images.

The two images would agree more if the color scales were the same. On the iPad using ADS-B weather, the colors decode as: light green is 20-30 dBz, dark green is 30-40 dBz, yellow is 40-45 dBz and amber is 45-50 dBz. On the MFD, green is 20-30 dBz, yellow is 30-40 dBz, and red is 40-50 dBz. (The color scales are different for internet-based weather. Check the manual for whatever app you use to know what colors equate to in dBz for all situations.)

The danger zone is usually considered to be 40 dBz and higher, so staying clear of the yellow on the iPad is a usually good policy. But the MFD paints yellow for 30-40 dBz returns that might be fine to fly though, and that the iPad would paint dark green.

Given the differences in radar color scales, it, now, makes sense that the iPad displays a wide swath of dark green with bits of yellow to the right of the airplane, while the MFD displays a wide area of yellow with bits of red in the same locations. The largest area of red on the MFD (on that dashed, curved distance ring) is the same return as the yellow and orange shown on the iPad (furthest right of the screen, just to the right of ACOVE).

DBz isn’t the only factor worth considering. The distance between the “contour lines” reveal how much the dBz increases in intensity over a certain distance. The greater the change in intensity over a shorter distance, the greater the hazard. On this flight, the distance between contour lines is relatively wide–that’s pretty benign.

Even after all this alignment, there’s still a discrepancy. The iPad shows yellow and amber by V213 and V489 — a no-fly of over 40 dBz on ADS-B dBz scales — yet the MFD shows some yellow (30-40 dBz) surrounded by green (20-30 dBz), which I’d been flying through for nearly two hours. Remember, yellow and amber on my iPad would be red on the MFD. So, there’s an area I refuse to cross using only the iPad, but would bisect without much concern using only the MFD. That’s a little spooky.

Which display was right? Beats me. I could have asked ATC, but I didn’t. That might have shed light, or the controller might have called it “light to moderate precip,” leaving me as uncertain as before.

The takeaway is that all such information should be considered an educated opinion, not a fact. It’s data that’s been collected from various sources, processed automatically, checked by a human briefly, and then pumped out to our cockpits. It’s neither completely right nor completely wrong. And, of course, NEXRAD mosaics shouldn’t be used for sole-source choices on navigating any kind of weather, especially for close-in tactical decisions.

Having that extra info sure beats just watching the clouds get darker, though.

Watch This Video

Misleading Lightning

Stormscopes don’t seem as common as they once were, and that’s too bad because they’re a great adjunct to NEXRAD. A sferic device like a stormscope does a great job showing the relative bearing of the electrical activity, but it’s not always so hot on distance. Stronger lightning strikes appear closer to the aircraft than they really are. Weak ones appear further away than they really are — and, from the perspective of light aircraft, no lightning should be considered weak.

By combining the lightning and the NEXRAD, you get a better picture. The bearing to the lightning should also be the bearing to the cell that generated it. If the lighting is between you and the cell, in apparently clear air, it’s likely those strikes are extra-strong, and that cell should be given extra distance. It’s also possible there’s activity in that spot but it’s growing fast and the NEXRAD isn’t painting any precip yet. Either way: Stay far away.

ForeFlight Question of the Month

https://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/10144740/Our-Faith-in-NEXRAD.png10001250Jeff Van Westhttps://media.ifrfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/14115136/IFR-Focus-Logo_White_Blue_Web-01.pngJeff Van West2025-09-16 08:55:562025-09-16 11:43:49Our Faith in NEXRAD

Video Tip: How to Fly an LPV Approach with a Garmin GTN 650

/by IFR Focus TeamFor many IFR pilots today, flying a GPS approach is second nature. Among the most capable options is the LPV approach, which offers ILS-like lateral and vertical guidance—but with far wider availability. Thanks to WAAS-enabled GPS, pilots can fly precision-style approaches at thousands of airports that don’t have an ILS installed.

In this video tip from Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course, we’ll break down the key differences between a GPS LNAV and LPV approach, and demonstrate step-by-step how to fly an LPV using the Garmin GTN 650 navigator.

Ready to sharpen your IFR skills even further? Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course combines over 13 hours of in-flight HD training with powerful written test prep tools—everything you need to build confidence and earn your rating.

Don’t Just Read the Notes—Use Them

/by James OniealScenario

Picture this: you’re flying an ILS approach right down to the absolute minimums. At 200 feet above the ground, the only thing you can see are the approach lights flashing through the fog. You quickly run through FAR 91.175 in your head and remind yourself: yep, this means you’re allowed to keep going down to 100 feet above the touchdown zone.

As you pass through 100 feet AGL, the runway threshold and touchdown zone lights start to poke through the fog—just enough to line things up. You glance left to check the PAPI and, at the same time, keep an eye on your instruments. That’s when you notice something weird: the glideslope says you’re right on path, but the PAPI shows you’re just a little low.

So now you’ve got a decision to make:

• Do you trust the instruments and continue to land?

• Or do you play it safe and go around?

Hard IFR vs. the Checkride

This is where real-world IFR flying separates itself from the checkride. The ride feels almost scripted: constant vectors to final, the same familiar approaches, and airports you’ve probably flown into before, even in VFR. You usually know the terrain, the obstacles, and what to expect.

But out in the real world, you don’t always get that luxury. Sometimes you’re flying into an unfamiliar airport, with little margin for error, and the only thing that keeps you ahead of the airplane is a solid approach briefing. And that briefing really should start well before you even sit down in the cockpit.

Why the Notes Section Matters

One of the most overlooked parts of the approach plate is the notes section. A lot of pilots skim right past it, but that’s where some of the most important “gotchas” are hiding—the limitations, restrictions, and curveballs that could turn an otherwise normal approach into an unexpected go-around.

If you take just a little extra time to brief those notes, you’ll head into the approach with clear expectations, less confusion, and fewer last-second decisions when workload is already maxed out.

Turning Notes into Action

One of the easiest examples is when you see:

One of the easiest examples is when you see:

I’ve heard plenty of pilots brief that by simply reading the words out loud, but that doesn’t really prepare you for what it means when you break out. A better way is to dig a little deeper. Compare the threshold crossing height (TCH) of the VGSI (like the PAPI or VASI) with the TCH listed for the ILS glideslope in the profile view.

Now you can brief it with actual meaning:

The Payoff

See the difference? By briefing exactly what you expect to see, you’ve removed uncertainty from the picture. You know what’s normal, you know what’s not, and you know what action to take. That’s how you avoid hesitation in a high-stress, low-visibility moment. Instead of just reading a note, you’ve turned it into a practical risk management tool.

👉 Want a simple way to make your own approach briefings clear and organized? Check out this video where I walk through the ILS10R Approach into the Columbus International Airport (KCMH). Use it as a template the next time you fly IFR, and you’ll never look at the notes section the same way again.

Instrument Maneuver Spotlight: Instrument Takeoff

/by IFR Focus TeamWelcome to the latest edition of the Instrument Maneuver Spotlight series. Here we’ll highlight the various maneuvers you’ll practice during your instrument training and be expected to demonstrate during your checkride.

When the weather’s down and the runway is disappearing into the clouds, you can’t rely on outside references to stay on centerline and maintain control. That’s where the instrument takeoff comes in. In this maneuver spotlight, we’ll break down the step-by-step technique for conducting a safe and precise instrument takeoff.

Each maneuver is part of Sporty’s Instrument Rating Course and includes a narrated video animation, along with step-by-step instructions that include performance standards and common errors. Study them while on the ground or print them for quick reference in the airplane.

New Interactive Series: What’s Wrong?

/by Pilot WorkshopsWelcome to “What’s Wrong?“, a new twist on aviation challenge quizzes. “What’s Wrong?” works just like a real flight: You’re in an airplane, flying along and there are clues to a potential problem right there in front of you—but it’s still on you to notice them and take action before it’s too late.

Ask the IFR Expert: When Can You Legally Log an Instrument Approach?

/by IFR Focus TeamUnder 14 CFR §61.57(c), instrument-rated pilots need to log at least six IAPs every six months to stay current and act as PIC under IFR or in weather below VFR mins. But not every approach counts—what matters are the conditions under which you fly it. Based on FAA guidance (InFO 15012), here’s the breakdown on what makes an IAP “loggable.”

The Four Ways to Conduct and Log IAPs

You can meet the requirement using:

Key Conditions for Logging an IAP

To log it, the approach must meet all these criteria (from FAA legal interpretations):

Important Notes:

Real-World Examples

Take Our Survey

Have questions or a scenario to run by the IFR experts? Drop it in the comments or email us at IFRFocus@Sportys.com.

Our Faith in NEXRAD

/by Jeff Van WestIn my younger days, my concept of weather data in flight was watching the clouds get darker as I trundled along the VOR radial, and wondering how rough the next 30 minutes might get. Now, I feel naked without in-cockpit weather, and will ask for deviations around denser precip just to keep from spilling my coffee.

But such confidence can get a harsh reality check now and then. Let me share a story of a flight that could be titled, “A Man with Two Watches.”

The route was direct Albany VOR (ALB), when two hours of hand-flying through IMC looked like it would end. (Yeah, that’s a photo in a Cirrus with the autopilot off. It’s not digitally altered. We all need the practice to stay sharp.) The iPad in my lap displayed ADS-B weather with stronger returns right of my course. The smoothest ride might have been to head a bit left (north), before crossing over ALB as planned. However, the XM weather on the MFD displayed a 20-mile wide area of low-energy returns left of the course, implying that a course southeast of ALB offered the smoothest ride. The ideal path using the MFD as my guide would be right on the edge of what I’d purposefully avoid using the iPad.

This dilemma wasn’t life-and-death. Perhaps it wasn’t even even spilling-the-coffee or not. For simplicity, I just stayed on course to ALB, feeling equivalent bumps to driving down a dirt road. That’s not the point.

It’s concerning that with only one of the weather presentations, I might have asked for a deviation with complete confidence. Had the returns been stronger, that misplaced confidence would have had real consequences. Using only one of the NEXRAD images, I would have asked for different things. Surely, both displays can’t be correct. Or, can they?

Let’s eliminate some potential sources for the discrepancy. The weather was not a rapidly changing convective environment, and the timestamps on both NEXRAD images were nearly identical. Both were “composite” reflectivity but came from different weather providers. We tend to simplify our thinking of NEXRAD as “base” or “composite” as if base always shows returns from the lowest part of the sky and composite displays all returns from the ground to the stratosphere. It’s not that simple.

Base reflectivity usually means “lowest tilt” reflectivity. This angle has the best chance of showing rain that would reach the ground, but it isn’t always low — once the beam is 125 miles from the station, the lowest tilt of the radar is looking about 17,000 feet in the air. That’s one of the reasons it’s essential to combine images from multiple stations into a mosaic, which is a single NEXRAD image.

Composite reflectivity adds multiple scan angles into the mosaic, but not necessarily all of them. What data is included — and what is left out — is part of the “secret sauce” different weather providers use, and part of the reason why we may see such different images.

The radar images, also, might not be as different as they first appear. The orientation on the MFD was heading-up. The iPad was track-up, but I had panned around, so now it was on some odd orientation. The MFD had a current direct-to ALB after a previous deviation. The iPad still displayed an old course because it hadn’t been updated.

When you rotate and scale the iPad image to match the MFD (above), the two images better align. The iPad still displays heavier returns where the MFD displays fewer, but the gaps line up better, and the logic of just staying on the course to ALB looks more consistent. Note to self: Think hard about the map scale and orientation when making any weather deviation based on in-cockpit images.

The two images would agree more if the color scales were the same. On the iPad using ADS-B weather, the colors decode as: light green is 20-30 dBz, dark green is 30-40 dBz, yellow is 40-45 dBz and amber is 45-50 dBz. On the MFD, green is 20-30 dBz, yellow is 30-40 dBz, and red is 40-50 dBz. (The color scales are different for internet-based weather. Check the manual for whatever app you use to know what colors equate to in dBz for all situations.)

The danger zone is usually considered to be 40 dBz and higher, so staying clear of the yellow on the iPad is a usually good policy. But the MFD paints yellow for 30-40 dBz returns that might be fine to fly though, and that the iPad would paint dark green.

Given the differences in radar color scales, it, now, makes sense that the iPad displays a wide swath of dark green with bits of yellow to the right of the airplane, while the MFD displays a wide area of yellow with bits of red in the same locations. The largest area of red on the MFD (on that dashed, curved distance ring) is the same return as the yellow and orange shown on the iPad (furthest right of the screen, just to the right of ACOVE).

DBz isn’t the only factor worth considering. The distance between the “contour lines” reveal how much the dBz increases in intensity over a certain distance. The greater the change in intensity over a shorter distance, the greater the hazard. On this flight, the distance between contour lines is relatively wide–that’s pretty benign.

Even after all this alignment, there’s still a discrepancy. The iPad shows yellow and amber by V213 and V489 — a no-fly of over 40 dBz on ADS-B dBz scales — yet the MFD shows some yellow (30-40 dBz) surrounded by green (20-30 dBz), which I’d been flying through for nearly two hours. Remember, yellow and amber on my iPad would be red on the MFD. So, there’s an area I refuse to cross using only the iPad, but would bisect without much concern using only the MFD. That’s a little spooky.

Which display was right? Beats me. I could have asked ATC, but I didn’t. That might have shed light, or the controller might have called it “light to moderate precip,” leaving me as uncertain as before.

The takeaway is that all such information should be considered an educated opinion, not a fact. It’s data that’s been collected from various sources, processed automatically, checked by a human briefly, and then pumped out to our cockpits. It’s neither completely right nor completely wrong. And, of course, NEXRAD mosaics shouldn’t be used for sole-source choices on navigating any kind of weather, especially for close-in tactical decisions.

Having that extra info sure beats just watching the clouds get darker, though.

Watch This Video

Misleading Lightning

Stormscopes don’t seem as common as they once were, and that’s too bad because they’re a great adjunct to NEXRAD. A sferic device like a stormscope does a great job showing the relative bearing of the electrical activity, but it’s not always so hot on distance. Stronger lightning strikes appear closer to the aircraft than they really are. Weak ones appear further away than they really are — and, from the perspective of light aircraft, no lightning should be considered weak.

By combining the lightning and the NEXRAD, you get a better picture. The bearing to the lightning should also be the bearing to the cell that generated it. If the lighting is between you and the cell, in apparently clear air, it’s likely those strikes are extra-strong, and that cell should be given extra distance. It’s also possible there’s activity in that spot but it’s growing fast and the NEXRAD isn’t painting any precip yet. Either way: Stay far away.

ForeFlight Question of the Month