Practical IFR: Does Your Approach Use the Wrong Minimums?

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It’s a dark and stormy night. You’re instrument current and proficient. Your bird is well equipped. But you’re concerned because the reported ceilings have been going up and down on both sides of the published minimums.

To which I say, “Who cares?”

Seeing Is What Matters

Put yourself on the approach and descending. You will either break out to see something, or you won’t. It’s binary; one or the other. If you see nothing before the prescribed moment arrives, you commence the missed approach. Simple.

If you see something … well, now you must judge.

And there’s the key. It’s visibility that controls whether we can land or not. While on paper that’s a number we have or don’t, it’s not so simple in real life. We must make a rapid judgment call—sometimes based on a glance—as to whether we’re getting enough visual information to call the flight visibility half a mile. Or three-quarters of a mile, or two miles, or whatever.

That’s why I want to know what I expect to see when that moment arrives. Am I expecting the approach lights with a green threshold and not much more? Am I expecting half a runway visible, but 20 degrees left of my nose?

I think it’s our training where we don foggles, fly down to an altitude, and then go missed that gets us so focused on altitude. In real IFR, what we need to be focused on is distance: When we get down to X, how far should we be able to look and see Y?

This kind of thinking also allows for a certain consistency. Fly the approach to DA/MDA, period. Somewhere along the way, visibility should get high enough that we can continue past DA/MDA for landing. we note the visibility coming into view—and continue on the approach until it’s operationally beneficial to think “landing.” When vis is really low, that’s probably about 50 feet AGL.

When I read NTSB reports, the instrument approach crashes seem to fall into two categories: grossly botched at altitudes well above the +500 or even +1000 people set as personal minimums, or unknown flying into the trees or approach lights at the very end of the approach. Ceilings weren’t the issue on the first ones, but visibility is a likely culprit on the latter. I think we do ourselves a disservice assuming these are “duck unders” where pilot descended too low. I’ll wager an overpriced 4-pack of craft beer the majority were continuing past DA or MDA into questionable visibility that wasn’t IMC … but wasn’t sufficient to safely find pavement. This phenomenon might get worse rather than better given the prevalence of following an advisory glidepath on LNAV-only approaches. It’s super tempting to continue past MDA with just enough visibility to convince yourself you can find the runway, but not quite enough visibility to make it a sure thing.

That’s why I’ll happily try an approach where the AWOS is calling a bit below minimums for DA or MDA, so long as the visibility is good beneath. It’s also why I won’t bother with an approach with visibilities too low for likely completion, even if the ceilings are several hundred feet above the published minimum. Not sure you agree with this thinking? Here’s a challenge for you: Fly a given approach both ways in a simulator with decent visuals. Make it something other than an ILS or LPV with 200-foot and 1/2-mile mins for clarity. See which one you feel more confident about.

Commercial operations usually work the same way; visibility rules.

Sure, there’s value in noting the ceiling versus MDA/DA to see if there’s even a chance, but if it’s close, go for it. While I don’t particularly buy in to personal minimums at all, if I was setting a personal minimum for approaches, it would be by visibility, not ceiling.

Maybe you don’t really worry about visibility at the end of an approach? If you can see some runway, you just land? Your call, but that really is in violation. And while I will admit to knowing it’s possible to find the runway and land in RVR 800, I only do so knowing the statue of limitations is up on that knowledge. And I swear the flight visibility was higher. Really.

But now I’m (luckily) older and (thankfully) wiser. Today, visibility is what matters.

Watch This Video

Lower Your Personal Minimums

Canadians See It Differently

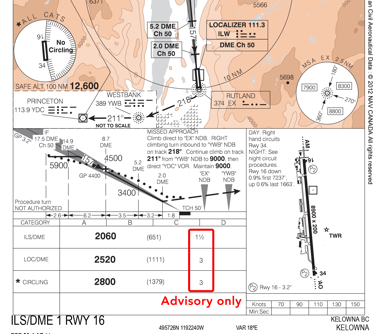

Fly in that country north of the border and this discussion changes in regulation, if not in practice. In Canada, prior to the FAF, visibility is controlling for both commercial operators and GA. The details are complicated, but roughly, commercial operators need 50 to 75 percent of the published visibility minimums to commence the approach. GA operators need at least RVR 1200 or 1/4 mile visibility. (Again, I’m being broad-brush here.)

Once past the FAF, however, the published visibilities on Canadian approach plates, “are advisory only. … They are not limiting and are intended to be used by pilots only to judge the probability of a successful landing.” In Canada, if you reach DA/MDA, can see the runway environment at all, and decide there’s enough visual information to land successfully, you can go for it.

However, I agree completely with my friend and Canadian pilot David Gagliardi when he says, “Why on earth would you continue any approach when the visibility is less than a quarter mile? The chances of you successfully completing it are basically zero; the chances of dying are not zero.”

ForeFlight Question of the Month

- Practical IFR: Off-Route Thinking - November 18, 2025

- Practical IFR: Don’t Disable. Revert! - October 14, 2025

- Our Faith in NEXRAD - September 16, 2025

Jeff, I think what gets lost in translation when teaching approaches is exactly what you are talking about: Every single approach ends visually vis-a-vis landing is a visual maneuver. And if you look at what 91.175(c) is trying to do (really) is an attempt to “legally gate what acceptable visibility” really means outside of just a number (and it should be pointed out that I believe visibility in flight is always ruling over what is reported at least from a Part 91 perspective).

If you think about the purpose of any approach, it’s to get down, right? But I think you would agree, more importantly it is to leave you at a point in space where you can see (operative word here) the runway environment and reasonably land given the minimums for your category of aircraft, i.e. have the viz.

Precision approaches have DA’s because they typically get you down lower at the cost of, well, getting lower, so the decision to go-missed should be immediate given where you are in space, while a non-precision approach sacrifices height for potentially more time to peek down. But in both cases, it is far more likely that the the visibility makes or breaks the approach. And as you said, probably a lot of bad things have happened more so when visibility is really low vs. low ceilings.

While I agree Jeff that visibility is the controlling factor from an operational standpoint, knowing the ceiling height prior to the approach or even during your preflight is the key to determine if you will even have an opportunity to see the runway environment. If you are in the clouds at the MDA or DH, it really doesn’t matter what the visibility is below those clouds. I am personally not going to try to execute a “look and see” approach if it is unlikely I will be able to land and most of the time this is all about ceiling height, not visibility. Sure, if I am doing a “practice approach” to this airport with a missed, not a problem. But if my intention is to land at this airport, I’m going somewhere else to avoid burning fuel and wasting time.

And, I am a huge proponent of personal minimums. Wrote an entire dissertation on why they are important and developed an app around them. This is a way that pilots can quantify risk. Pilots who understand the difference between what is “smart” or “safe” based on pilot experience and proficiency establish personal minimums that are more restrictive than the regulatory requirements.

Agree with that Scott. I’m just saying that the leading number on a personal minimum should be the lowest visibility you’ll accept for a given kind of approach. The ceilings could follow, but more as an objective line as to whether you will give it a shot. Most personal minimums I hear from people a ceiling-first or ceiling-only.

Jeff, taking a look down to minimums is certainly reasonable for those of us in the part 91 world, but… I think like everything else, its nuanced. Are the bases a broken layer or solid overcast? Is it day or night? Are you in the mountains? How advanced are your avionics? Are you landing after a 45minute or 4 hour flight? Do you really have your A game on this flight or are just solidly OK? Bottom line is risk has many variables and is constantly changing.

I agree with with this. Several factors to deal with. But for me the one overriding factor is visibility. If below 2 miles, everything else becomes moot and it is a no-go for even CONSIDERING/evaluating the other variables for attempting the approach.

Regarding visibility, I’m a fan of using approach lights to approximate distance, assuming that the runway has that option, and I always seek this information out when briefing an approach.

For example, while GA flying typically doesn’t involve approach light systems such as ALSF-1 or ALSF-2 (which extent to about 3000 feet), and we’ll exclude red terminating bars and such for this discussion, MALSR’s however are very common and extend to about 1500 feet. So if I can see ‘about two MALSR’s length’ at DA for an ILS or APV approach, that’s 3000 feet or ballpark 1/2 mile and for the ILS usually good to continue the approach, maybe not for the APV.

Personal minimums — 4 MALSR’s or a mile would be great. Below that depends on terrain, obstacles, what the visibility restriction is (rain, defined layer vs patchy), etc.

For a non-precision approach, with a VDP (published vs calculating your own but far enough out to make a stabilized descent), at the VDP you would obviously need to see the runway to continue. But for those who still dive and drive, using the ALS system at any point along the MDA you would need ‘X times MALSR’s 1500′ vs visibility required into the distance to keep going.

Continuing the approach, white cross-bars are 1000 feet from the threshold, so on any type of approach at this distance (on the glideslope/glidepath or well below an MDA), you would need to visualize well beyond the AIMING POINT MARKER (1000’ from threshold) to continue.

Basic point – given these distance reference markers, a ballpark assessment can be made regarding flight visibility.

Good idea? Bad idea? Too much thinking? Any comments appreciated.