It’s Personal: Managing Your Own Minimums

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

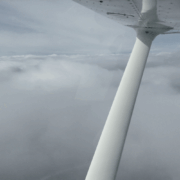

The conditions we accept for a flight – like how low we’ll descend in IMC – are truly personal. Among GA instrument pilots, there’s a wide range of what they’re willing to do, and happily most are respectful of their “personal minimums.” This risk-management system is ubiquitous and now has a larger presence in training standards. It even has its own chapter in an FAA handbook (more on that later). However, in the day-to-day, this doesn’t get the care and feeding it should, and when it does, the methods of use vary just as much as the “minimums” pilots set for themselves.

The wide range of personal minimums isn’t a problem per se – we all differ in our missions, aircraft, and risk tolerance. The problem is that it’s often created as a fill-in-the-blanks document (usually at the prodding of the CFI-I giving an IPC). This soon finds its way to the bottom of the electronic or physical flight bag. Over months or even just weeks, those numbers are forgotten or outdated unless a pilot flies regularly and under similar conditions. Another related issue is that personal minimums are treated as a snapshot of one’s present comfort level, and not as a “proficiency gauge” that requires monitoring and action. Thinking about personal minimums as more of a flight instrument, with ranges and limits, is a better way to check proficiency and, in the end, manage risk.

Limits and Ranges

Minimums are inherently built into the system, so we do pay a lot of attention to what we’d accept for visibility, ceilings, and certain operations like instrument departures. The FAA’s Risk Management Handbook (FAA-H-8083-2A edition) has a chapter on Personal Minimums, offering a step-by-step guide to make your own. This is a great start, especially for those working on the instrument rating. It discusses more than visibility-ceiling considerations, with items like turbulence, terrain, and personal health. We can build on this by viewing minimums as “Limitations” and adding a personal “Operating Range” for your missions.

Start with the Red Line, or Things You Don’t Do. Most of us don’t conduct 0-0 takeoffs even if legal for Part 91 operations (good call). Now: What’s your yellow range, or green? Depends. Say you’re OK flying to approach minimums; you use those for the departure runway in case of an emergency return. Put that together with the estimated ceiling at which you’d break out at the final approach fix to make a “yellow caution range” for a given runway, and weather above that as green. You’ll more carefully consider all the factors before accepting that departure; or maybe this time you want to be in the green arc. This method works for IFR approaches in general.

This mindset applies beyond routine operations. Abnormal or emergency operations can have operating ranges, too. Another common red line: flying to an airport where a circle-to-land at MDA is the only way to get in. Consider your own green arc, even if it has to be clear-and-10. Keep in mind that “never-do” doesn’t mean “never-practice” – in fact, this is something you should practice in safe conditions (under training if need be). Of course, circling approaches are required for an IPC, and it’s a great emergency skill – something you would never do unless, well, you have to.

Quick Poll

Moving Needles

Then, make this part of post-flight routines and carry it into the next pre-flight. When you log flights, include remarks on the vis, ceiling, winds, runway length, approach type, etc. and if you want, email it to yourself and take a look the next day. Was it comfortable on that approach, or were you white-knuckled during vectors? Would you happily do it tomorrow? If no, consider what makes it “yes” and adjust accordingly. It’s likely something will happen eventually that changes your comfort level, brings your attention to a skill gap, or has you gaining confidence flying that long route. This also helps avoid “limit creep,” a common downside to plain-old personal minimums in which landing a knot past your stated crosswind limit can start a trail of complacency. You weren’t suddenly unsafe going from 15 to 16 knots, so 17’s OK…we’d never treat Vne that way. So while respecting the confines of your envelope, watch for trends up or down in your skills over time and make adjustments for the future, not for today’s trip. That’s good risk management.

This approach to personal operating ranges and limitations can also include the flexibility we all want from our flying. Much like aircraft performance varying with weight, altitude, and weather, any particular mission will have custom parameters. You might still have that same weather red line for the next IFR trip, but maybe the green arc is wider since you’re flying with another pilot. Or you agree to fly to a new destination because you’ve tightened up the yellow range for weight to maximize fuel.

The Skill Gauge

Like the circling MDA example, regular training and practice to the highest level of proficiency you can achieve above your personal real-flying envelope will make the best use of those limits. That’s a never-ending process, of course; we’ll never run out of things we need to work on. But why train to approach minimums if we choose not to fly in low weather? First, this automatically widens the risk margin. A big green arc means your IFR comfort level isn’t on the edge, which can only make flying more fun. And it can save your life if something unexpected happens and you’re able to manage that as comfortably as possible.

And it’s built into the requirements for maintaining currency. The FAA’s InFo 15012 on “Logging Instrument Approach Procedures (IAP)” provides guidance on when you can log approaches. One often-overlooked requirement is when practicing in flight under simulated IMC, you must fly to the MDA or DA/DH before going missed or “breaking out.” If traffic or other hazards prevented this but you did fly past the FAF, you can still log it. So in practice, you’re going for maximum proficiency, to the fullest extent of your privileges.

We mentioned “gauge” earlier; think of your skill level as a fuel gauge – decreases in proficiency empty the tank, while solid skills fill it back up. And you don’t want to go empty, or even close to it. The nice system you’ve built now has limits, ranges, and ways to monitor it without making impulsive changes. In addition to post-flight briefings, it’s helpful to review the whole thing on a periodic schedule, such as during your annual inspection (something to do when the aircraft’s out of service) or an annual IPC (another good idea). Maybe you’re making an equipment change soon, or your flying habits will change. Even if everything’s on a steady track for the foreseeable future, a regular checkup of personal limitations and operating ranges is great confirmation that you are indeed getting the most out of your instrument ticket.

- The Anti-PIC - January 13, 2026

- It’s Personal: Managing Your Own Minimums - November 11, 2025

- Decisions on the Fly - September 2, 2025

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!