Fronts, Freezing Levels, and Staying Out of Trouble This Winter

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

If you’re anything like me, the holidays are basically the last window to get some flying in before winter shows up and icing becomes a constant headache. A lucky few out there have aircraft certified for flight into known icing…but for most of us, that’s not the case. Instead of boots or TKS doing the heavy lifting, we end up relying on smart weather planning and a solid understanding of where the trouble spots are.

Instead of boots or TKS doing the heavy lifting, most of us rely on smart weather planning to avoid the winter weather hazards.

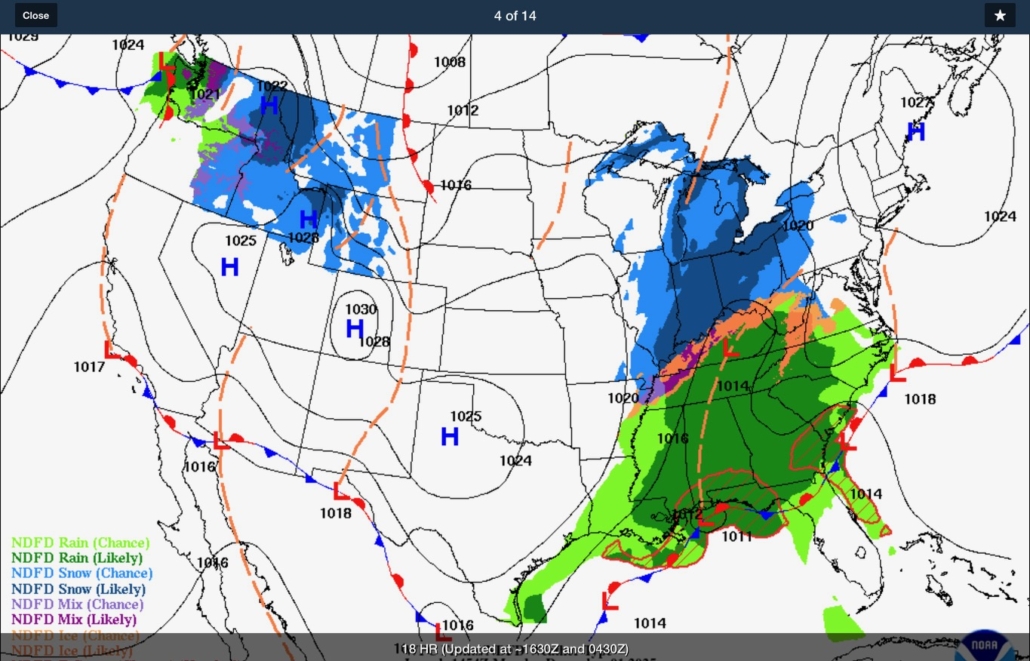

If you’re trying to squeeze in as much flying as you can this winter, there are a few things worth keeping in mind that can help keep you—and the people you care about—safe. One of my go-to tools this time of year is the Prog Chart section under Imagery in ForeFlight. The 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 36-, 48-, and 60-hour charts are especially helpful. Once you get used to reading them, they give you a sneak peek at how the big weather systems are lining up long before you see anything on radar.

I’m also a big fan of keeping things simple. The KISS principle works wonders in winter flying: stick close to high-pressure systems whenever you can. Sure, you may still deal with some high winds or wind shear depending on what fronts are around, but those are much easier to accurately measure and use for a go/no-go decision based on your personal mins.

Now, if you live or fly in an area that gets cold, low clouds once winter hits, here’s a big tip: do your best to avoid frontal systems, especially warm fronts and occluded fronts. They’re the icing all-stars—and not in a good way.

Here’s a quick, plain-English breakdown of what to watch for:

1. Warm Fronts: The Kings of Widespread Icing

Warm fronts are hands-down the biggest troublemakers when it comes to winter icing.

Why they’re bad:

-

Warm air slides over cold air and creates a nice, deep, soggy layer.

-

You get multiple cloud decks, all sitting in prime icing temps.

-

Icing can start 100 miles or more ahead of where the front actually is.

-

Freezing rain, drizzle, supercooled liquid droplets (SLD)—basically all the stuff we don’t want.

2. Occluded Fronts: The Deep, Layered Icing Machines

Occlusions basically mash together the worst parts of warm and cold fronts, and the result is a monster icing setup.

Why they’re bad:

-

You get warm-front overrunning and cold-front lift at the same time.

-

Cloud layers and precipitation can stack up 20,000 feet deep.

-

Icing usually spans a huge altitude range, making climb/descend options limited.

3. Cold Fronts: Short-Lived but Sneaky

Cold fronts aren’t as widespread as the other two, but don’t underestimate them.

Why they’re bad:

-

Strong lift can build clear ice in a hurry.

-

They move fast, so you can get caught between layers during climb or descent.

-

After the front passes, that “leftover” stratocumulus can hold supercooled droplets.

If you plan on flying as we continue into winter, be careful out there, monitor the ceilings and freezing levels, and stay ahead of problems by diving into those Prog Charts. Fly safe, and happy holidays!

- Fronts, Freezing Levels, and Staying Out of Trouble This Winter - December 9, 2025

- Don’t Just Read the Notes—Use Them - September 30, 2025

- Too Much Info: How to Focus IFR Thinking - August 12, 2025

And

* think twice about flying at night

*leave strobe on so you know when you’re in clouds/possible precip

*extra flashlights

*immediate 180 if ever in ice

*hand fly don’t rely on AP in ice

*

Thanks James! Very useful guidance (concise, stays on point, KISS principle). … saved for quick reference!